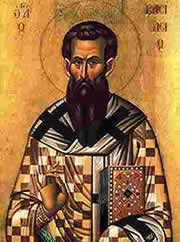

Basil the Great (c 329-379)

One of the Cappodician Fathers

|

Basil the Great was born in Cæsarea, A.D. 329. His family were wealthy Christians. His grandmother Macrina, and his mother, Emmelia, were canonized. His brothers, Gregory of Nyssa, and Peter of Sebaste, and his sister Macrina are all saints in both the Greek and the Roman churches. His was a most lovable and loving spirit. His works abound in descriptions of the beauties of nature, which is something rare in ancient literature, outside the Bible. He resided for many years in a romantic locality, with his mother and sister. A.D. 364, against his will, he was made presbyter, and in 370 was elected bishop of Cæsarea. He died A.D. 379.

He devoted himself to the sick, and founded the splendid hospital Basilias, for lepers, of whom he took care, not even neglecting to kiss them in defiance of contagion. He stands in the highest group of pulpit orators, theologians, pastors, and rulers, and most eminent writers and noble men of the church's first five hundred years.

Basil's Language

Basil says: "The Lord's peace is co-extensive with all time. For all things shall be subject to him, and all things shall acknowledge his empire; and when God shall be all in all, those who now excite discord by revolts having been pacified, shall praise God in peaceful concord."

On the words in Isaiah 1:24, "My anger will not cease, I will burn them," he says, "And why is this? In order that I may purify."

Basil was "the strenuous champion of orthodoxy in the East, the restorer of union to the divided Oriental church, and the promoter of unity between the East and the West." Theodoret styles him "one of the lights of the world."

Among other quotable passages is this: "For we have often observed that it is the sins which are consumed, not the very persons to whom the sins have befallen."

But there are passages to be found in Basil susceptible of sustaining the doctrine of interminable punishment. This great theologian was infected with the wretched idea prevalent in his day, that the wise could accept truths not to be taught to the multitude. But the brother of, and co-laborer with, Gregory of Nyssa, and the "Blessed Macrina," he could but have sympathized with their awe inspiring faith.

Cave's Error

Cave scarcely alludes to Basil's views of destiny, but faintly suggests the truth when he says:

"For though his enemies, to serve their own ends by blasting his reputation, did sometimes charge him with corrupting the Christian doctrine, and entertaining impious and unorthodox sentiments, and that too in some of the greater articles, yet the objection, when looked into, did quickly vanish, himself solemnly professing upon this occasion, that however in other respects he had enough to answer for, yet this was his glory and triumph, that he had never entertained false notions of God, but had constantly kept the faith pure and unviolated, as he had received it from his ancestors."

Remembering his sainted grandmother, Macrina, and his spiritual fathers, Origen and Clemens Alexandrinus, we can understand his disclaimer.

Notwithstanding Basil's probable belief in the final restoration, he employs as severe language in reference to the sinner's sufferings so do any of the fathers who have left no record on the subject of man's final destiny.

He says: "With what body shall it endure those interminable and unendurable scourges, where is the quenchless fire and the worm punishing deathlessly, and the dark and horrible abyss of hell, and the bitter groans, and the vehement wailing, and the weeping and gnashing of teeth, where the evils have no end."

Eulogies of Basil

He is said to have had learning the most ample, eloquence of the highest order, argumentative powers unsurpassed, literary ability unequaled, "a style of writing admirable, almost matchless, proper, clearly expressed, significant, soft, smooth and easy, and yet persuasive and powerful;" as a philosopher as wise as he was accomplished as a theologian.

Erasmus gives him the pre-eminence above Pericles, Isocrates and Demosthenes, and ranks him higher than Athanasius, Nazianzen, Nyssen and Chrysostom. And Cave exhausts eulogy and praise in describing his "moral and divine accomplishments," and closes his account by saying: "Perhaps it is an instance hardly to be paralleled in any age, for three brothers, all men of note and eminency, to be bishops at the same time." He might have added--and with a sister their full equal.

Basil's grand spirit can be seen in his reply to the emperor, when the latter threatened him, should he not obey the sovereign's command. His noble answer compelled the emperor to forego his purpose. Basil said he did not fear the emperor's threats; confiscation could not harm one who only possessed a suit of plain clothes and a few books; he could not be banished for he could not find a home anywhere, as the earth was God's, and himself everywhere a stranger; his frail body could endure but little torture, and death would be a favor, as it would only conduct him to God, his eternal home.

The Mass of Christians Universalists

Basil says in one place, in a work attributed to him, "The mass of men (Christians) say that there is to be an end of punishment to those who are punished." If the work is not Basil's, the testimony as to the state of opinion at that time is no less valuable: "The mass of men say that there is to be an end of punishment."

By J.W. Hanson (Excerpt from "Universalism, the Prevailing Doctrine of the Church for its First 500 Years")

Back to Tracing Universalist Thought Index