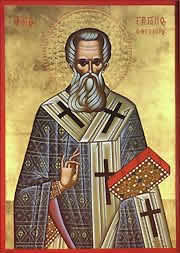

Gregory of Nazianzen (c 330-391)

One of the Cappodician Fathers

|

Gregory Nazianzen, Bishop of Constantinople

Gregory of Nazianzus was one of the greatest orators of the ancient church. Gibbon sarcastically says: "The title of Saint has been added to his name, but the tenderness of his heart, and the elegance of his genius, reflect a more pleasing luster on the memory of Gregory Nazianzen."

The child of a Christian mother, Nonna, he was instructed in youth in the elements of religion. He enjoyed an early acquaintance with Basil, and in Alexandria with Athanasius. With Basil his friendship was so strong that Gregory says it was only one soul in two bodies.

A.D. 361, he became presbyter (elder), and in 379 he was called to the charge of the small, divided orthodox church in Constantinople, which had been almost annihilated by the prevalence of Arianism. He so strengthened and increased it, that the little chapel became the splendid "Church of the Resurrection." A.D. 380 the Emperor Theodosius deposed the Arian bishop, and transferred the cathedral to Gregory. He was elected bishop of Constantinople in May, 381, and was president of the Ecumenical council in Constantinople, while Gregory Nyssa added the clauses to the Nicene creed. He resigned because of the hostility of other bishops, and passed his remaining days in religious and literary pursuits.

He died A.D. 390 or 391. He was second to Chrysostom as an orator in the Greek church. More than this, he was one of the purest and best of men, and his was one of the five or six greatest names in the church's first five hundred years. Prof. Schaff styles him "one of the champions of Orthodoxy."

Gregory says: "God brings the dead to life as partakers of fire or light. But whether even all shall hereafter partake of God, let it be elsewhere discussed." Again he says: "I know also of a fire not cleansing but chastising, unless anyone chooses even in this case to regard it more humanely, and creditably to the Chastiser." This is a remarkable instance of the esoteric, and well may Petavius say: "It is manifest that in this place St. Gregory is speaking of the punishments of the damned, and doubted whether they would be eternal, or rather to be estimated in accordance with the goodness of God, so as at some time to be terminated." And Farrar well observes: "If this last sentence had not been added the passage would have been always quoted as a most decisive proof that this eminently great father and theologian held, without any modification, the severest form of the doctrine of endless torments."

The Penalties of Sin

Gregory tells us: "When you read in Scripture of God's being angry, or threatening a sword against the wicked understand this rightly, and not wrongly, how then are these metaphors used? Figuratively. In what way? With a view to terrifying minds of the simpler sort."

He writes again: "A few drops of blood renew the whole world, and become for all men that which condensation is for milk, uniting and drawing us into one." Christ is "like leaven for the entire mass, and having made that which was damned one with himself, frees the whole from damnation."

And yet Gregory describes the penalties of sin in language as fearful as though he did not teach restoration beyond it. He says: "That sentence after which is no appeal, no higher judge, no defense through subsequent work, no oil from the wise virgins or from those who sell, for the failing lamps; but one last fearful judgment, even more just than formidable, yea, rather the more formidable because it is also just; when thrones are set and the Ancient of Days sitteth, and books are open, and a stream of fire sweepeth and they who have done evil to the resurrection of judgment (where) the torment will be, with the rest, or rather above all the rest, to be cast off from God, and that shame in the conscience which hath no end."

The character of Gregory shows us the kind of mind that leans to the larger hope, or, perhaps, the disposition that the larger hope produces. Says Farrar: "Poet, orator, theologian; a man as great theologically as he was personally winning the sole man whom the church has suffered to share that title (Theologian) with the Evangelist St. John, the most learned and the most eloquent bishop in one of the most learned ages of the church, whom St. Basil called 'a vessel of election, a deep well, a mouth of Christ;' whom Rudinus calls 'incomparable in life and doctrine." Gregory of Nazianzus deserved the honor of sainthood if any man has ever done, being as he was, one of the bravest men in an age of confessors, one of the holiest men in an age of saints." "In questions of eschatology he seems more or less to have shared, though with wavering language, in some of the views of Origen, which the church has partly adopted and partially uncondemned--the view, especially, that there shall be hereafter a probatory and purifying fire, and that we may indulge a hope in the possible cessation, for many, if not for all, of the punishments which await sin beyond the grave. He speaks indeed far less openly than Gregory of Nyssa, of a belief in the final restoration of all things, but even this belief lies involved in his remarks on the prophecy of St. Paul, concerning the day when 'God shall be all in all.'"

Gregory's Spirit

When Gregory and his congregation had been attacked in their church, while celebrating our Lord's baptism, by the Arian rabble of Constantinople, in consequence of the report that they were Tritheists, Gregory heard that Theodorus was about to appeal for redness to Theodosius, whereupon the good man wrote that while punishment might possibly prevent recurrence of such conduct, it was better to give an example of long-suffering.

"Let us," said he, "overcome them by gentleness, and win them by piety; let their punishment be found in their own consciences, not in our resentment. Dry not up the fig-tree that may yet bear fruit." The Seventh General Council called him "Father of Fathers."

That he regarded punishment after death as limited, is sufficiently evident from his reference to the heretical Novatians: "Let them, if they will, walk in our way and in Christ's. If not, let them walk in their own way. Perchance there they will be baptized with fire, with that last, that more laborious and longer baptism, which devours the substance like hay, and consumes the lightness of all evil."

Neander says: "Gregory of Nazianzen did not venture to express his own doctrine so openly (as Gregory Nyssen) but allows it sometimes to escape when he is speaking of eternal punishment. The Antiochan school were led to this doctrine, not by Origen but by their own thinkings and examinations of the Scripture. They regarded the two-fold division of the development of the creature as a general law of the universe. This led to the final result of universal participation in the unchangeable divine life. Hence the was taught by Diodorus of Tarsus, in his treatise on the Incarnation of God, and also by Theodorus. He applied Matt. 5:26, to prove a rule of proportion, and an end of punishment. God would not call the wicked to rise again if they must endure punishment without amendment."

By J.W. Hanson (Excerpt from "Universalism, the Prevailing Doctrine of the Church for its First 500 Years")

Back to Tracing Universalist Thought Index