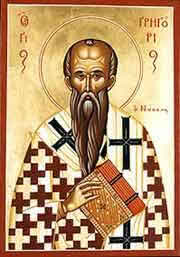

Gregory of Nyssa (c 335-390)

One of the Cappodician Fathers

|

From the time he was thirty-five until his death, Gregory of Nyssa, Didymus and Diodorus of Tarsus, were the unopposed advocates of universal redemption. Most unique and valuable of all his works was the biography of his sister, described in our sketch of Macrina. His descriptions of her life, conversations and death are gems of early Chrstian literature. They overflow with declarations of universal salvation.

Gregory was devoted to the memory of Origen as his spiritual godfather, and teacher, as were his saintly brother and sister. He has well been called "the flower of orthodoxy." He declared that Christ "frees mankind from their wickedness, healing the very inventor of wickedness."

He asks: "What is then the scope of St. Paul's argument in this place? That the nature of evil shall one day be wholly exterminated, and divine, immortal goodness embrace within itself all intelligent natures; so that of all who were made by God, not one shall be exiled from his kingdom; when all the mixtures of evil that like a corrupt matter is mingled in things, shall be dissolved, and consumed in the furnace of purifying fire, and everything that had its origin from God shall be restored to its pristine state of purity."

"This is the end of our hope, that nothing shall be left contrary to the good, but that the divine life, penetrating all things, shall absolutely destroy death from existing things, sin having been previously destroyed,"

"For it is evident that God will in truth be 'in all' when there shall be no evil in existence, when every created being is at harmony with itself, and every tongue shall confess that Jesus Christ is Lord; when every creature shall have been made one body. Now the body of Christ, as I have often said, is the whole of humanity."

On the Psalms, "Neither is sin from eternity, not will it last to eternity. For that which did not always exist shall not last forever."

His language demonstrates the fact that the word aionios did not have the meaning of endless duration in his day. He distinctly says: "Whoever considers the divine power will plainly perceive that it is able at length to restore by means of the aionion purging and atoning sufferings, those who have gone even to this extremity of wickedness." Thus "everlasting" punishment will end in salvation, according to one of the greatest of the fathers of the Fourth Century.

Gregory's Language

In his "Sermo Catecheticus Magnus," a work of forty chapters, for the teaching of theological learners, written to show the harmony of Christianity with the instincts of the human heart, he asserts "the annihilation of evil, the restitution of all things, and the final restoration of evil men and evil spirits to the blessedness of union with God, so that he may be 'all in all,' embracing all things endowed with sense and reason"--doctrines derived by him from Origen. To save the credit of a doctor of the church of acknowledged orthodoxy, it has been asserted from the time of Germanus of Constantinople, that these passages were foisted in by heretical writers. But there is no foundation for this assumption, and we may safely say that "the wish is father to the thought," and that the final restitution of all things was distinctly held and taught by him in his writings.

He teaches that "when death approaches to life, and darkness to light, and the corruptible to the incorruptible, the inferior is done away with and reduced to non-existence, and the thing purged is benefited, just as the dross is purged from gold by fire. In the same way in the long circuits of time, when the evil of nature which is now mingled and implanted in them has been taken away, whensoever the restoration to their old condition of the things that now lie in wickedness takes place, there will be a unanimous thanksgiving from the whole creation, both of those who have been punished in the purification and of those who have not at all needed purification.

"I believe that punishment will be administered in proportion to each one's corruptness. Therefore to whom there is much corruption attached, with him it is necessary that the purgatorial time which is to consume it should be great, and of long duration; but to him in whom the wicked disposition has been already in part subjected, a proportionate degree of that sharper and more vehement punishment shall be forgiven. All evil, however, must at length be entirely removed from everything, so that it shall no more exist. For such being the nature of sin that it cannot exist without a corrupt motive, it must of course be perfectly dissolved, and wholly destroyed, so that nothing can remain a receptacle of it, when all motive and influence shall spring from God alone," etc.

Perversion of Historians

The manner in which historians and biographers have been guilty of suppression by their prejudices or lack of perception to fact, is illustrated by Cave in his "Lives of the Fathers," when, speaking of this most out-spoken Universalist, he says, that on the occasion of the death of his sister Macrina, "he penned his excellent book ('Life and Resurrection,') wherein if some later hand have interspersed some few Origenian dogmata, it is no more than what they have done to some few other of his tracts, to give his thoughts vent upon those noble arguments." The "later" hands were impelled by altogether different "dogmata," and suppressed or modified Origen's doctrines, as Rufinus confessed, instead of inserting them in the works of their predecessors.

If Gregory has suffered at all at the hands of mutilators, it has been by those who have minimized and not those who have magnified his Universalism. But this aspersion originated with Germanus, bishop of Constantinople (A.D. 730), in harmony with a favorite mode of opposition to Universalism. In Germanus's Antapodotikos he endeavored to show that all the passages in Gregory which treat of the apokatastasis were interpolated by heretics.14 This charge has often been echoed since. But the prejudiced Daille calls it "the last resort of those who with a stupid and absurd persistance will have it that the ancients wrote nothing different from the faith at present received; for the whole of Gregory Nyssen's orations are so deeply permeated with the perncious doctrine in question, than it can have been inserted by none other that the author himself."15 The conduct of historians, not only of those who were theologically warped, but of such as sought to be impartial on the opinions of the early Christians on man's final destiny, is something phenomenal. Even Lecky writes: "Origen, and his disciple Gregory of Nyssa, in a somewhat hesitating manner, diverged from the prevailing opinion (eternal torments) and strongly inclined to the belief in the ultimate salvation of all.

But they were alone in their opinion. With these two exceptions, all the fathers proclaimed the eternity of torments." 16 It is shown in this volume that not only were Diodore, Theodore, and others of the Antiochan school Universalists but that for centuries four theological schools taught the doctrine. A most singular fact in this connection is the Prof. Shedd, elsewhere in this book, denies his own statement similar to Lecky's, as shown on a previous page. This is the testimony of Dr. Schaff in his valuable history:

"Gregory adopts the doctrine of the final restoration of all things. The plan of redemption is in his view absolutely universal, and embraces all spiritual beings. Good is the only positive reality; evil is the negative, the non-existent, and must finally abolish itself, because it is not of God. Unbelievers must indeed pass through a second death, in order to be purged from the filthiness of the flesh. But God does not give them up, for they are his property, spiritual natures allied to him. His love, which draws pure souls easily and without pain to itself, becomes a purifying fire to all who cleave to the earthly, till the impure element is driven off. As all comes forth from God, so must all return into him at last." "Universal salvation (including Satan) was clearly taught by Gregory of Nyssa, a profound thinker of the school of Origen."

In his comments on the Psalms, Gregory says: "By which God shows that neither is sin from eternity nor will it last to eternity. Wickedness being thus destroyed, and its imprint being left in none, all shall be fashioned after Christ, and in all that one character shall shine, which originally was imprinted on our nature." "Sin, whose end is extinction, and a change to nothingness from evil to a state of blessedness." On Ps. 57:1, "Sin is like a plant on a house top, not rooted, not sown, not ploughed in the restoration to goodness of all things, it passes away and vanishes. So not even a trace of the evil which now abounds in us, shall remain, etc." If sin be not cured here its cure will be effected hereafter. And God's threats are that "through fear we may be trained to avoid evil; but by those who are more intelligent it (the judgment) is believed to be a medicine," etc. "God himself is not really seen in wrath." "The soul which is united to sin must be set in the fire, so that that which is unnatural and vile may be removed, consumed by the aionion fire."17 Thus the (aionion) fire was regarded by Gregory as purifying. "If it (the soul) remains (in the present life) the healing is accomplished in the life beyond." (Orat. Catech.)

Farrar tells us: "There is no scholar of any weight in any school of theology who does not now admit that two at least of the three great Cappadocians believed in the final and universal restoration of human souls. And the remarkable fact is that Gregory developed these views without in any way imperiling his reputation for orthodoxy, and without the faintest reminder that he was deviating from the strictest paths of Catholic opinion." Professor Plumptre truthfully says: "His Universalism is as wide and unlimited as that of Bishop Newton of Bristol."

Opinions in the Fourth Century.

The Council of Constantinople, A.D. 381, which perfected the Nicene Creed, was participated in by the two Gregorys; Gregory Nazianzen presided and Gregory Nyssen added the clauses to the Nicene creed that are in italics on a previous page in this volume. They were both Universalists. Would any council, in ancient or modern times, composed of believers in endless punishment, select an avowed Universalist to preside over its deliberations, and guide its "doctrinal transactions?" And can anyone consistently think that Gregory's Universalism was unacceptable to the great council over which he presided?" Some of the strongest statements of Gregory's views will be found in his enthusiastic reports of Macrina's conversations, related in the preceding chapter, with which, every reader will see, he was in the fullest sympathy. Besides the works of Gregory named above, passages expressive of universal salvation may be found in "Oratio de Mortuis," "De Perfectione Christiani," etc.

"By the days of Gregory of Nyssa it (Universalism), aided by the unrivaled learning, genius and piety of Origen, had prevailed, and had succeeded in leavening, not the East alone, but much of the West. While the doctrine of annihilation has practically disappeared, Universalism has established itself, has become the prevailing opinion, even in quarters antagonistic to the school of Alexandria. The church of North Africa, in the person of Augustine, enters the field. The Greek tongue soon becomes unknown in the West, and the Greek fathers forgotten. On the throne of Him whose name is Love is now seated a stern Judge (a sort of Roman governor). The Father is lost in the Magistrate." 18

Dean Stanley candidly ascribes to Gregory "the blessed hope that God's justice and mercy are not controlled by the power of evil, that sin is not everlasting, and that in the world to come punishment will be corrective and not final, and will be ordered by a love and justice, the height and depths of which we cannot here fathom or comprehend." By J.W. Hanson (Excerpt from "Universalism, the Prevailing Doctrine of the Church for its First 500 Years")

More Quotes by Gregory of Nyssa

Back to Tracing Universalist Thought Index